In essence, doing the inner work means that if you’re stuck and want something to change, your first point of call is to work with your internal world of thoughts, beliefs, emotions, body and breath, before seeking to change something external to you.

If you only look for the answer to your problems outside yourself, you can get locked into a reactive and defensive mode of relating. Whereas instinctive reactions aren’t wrong, they keep you small and don’t address the root of your problems.

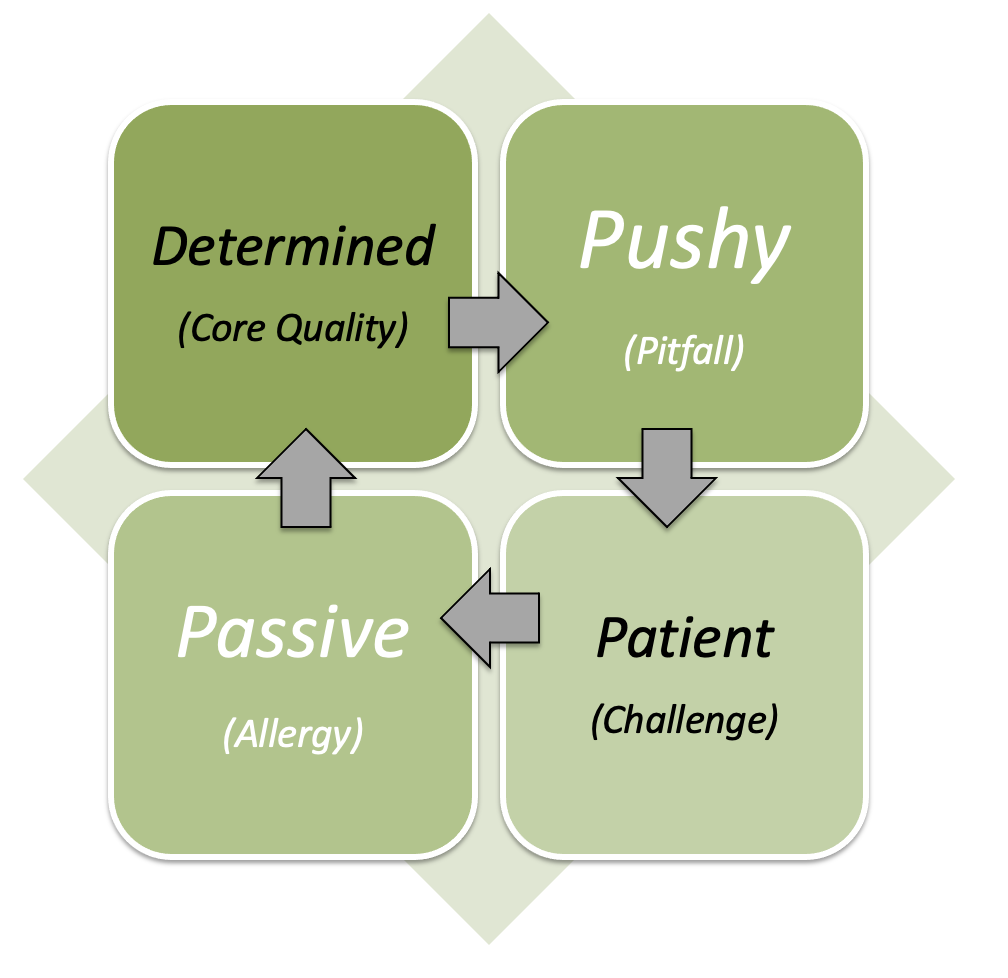

These examples relate to work, but we could easily come up with personal examples too. The patterns are the same. We react based on an emotional trigger, which can make matters worse. Not only that, we get into a downward spiral of negative thoughts causing us to accumulate stress and tension beyond what is healthy.

In another example you feel stressed and overworked. You have high standards, find it hard to delegate and don’t want to overburden your team. You thrive on praise from your managers, which makes it hard to say no to extra work. You secretly blame others for your situation and think to yourself “if only my workload would diminish, then I’d be happy. If only my team members had more capacity and were better skilled, then my stresses would melt away.”

Fixing your problems in the external world will give you temporary relief, but shifting them once and for all requires you to investigate which part of your programming is getting in your way. Do you believe for instance, that your self-worth is linked to how much you achieve at work? Do you believe that other people’s needs are more important than your own? And what do you do with the emotions that arise when you feel you’re not in control?

When we uncover the beliefs that are running us, and learn to question them, we can change our perception and our situation quicker than we think. I know that to be true. I was once an overworked manager who found it hard to self-regulate in emotionally challenging situations. Until we dare to question our operating system, we will continue to feel stuck and overwhelmed.

Doing the inner work can help us acknowledge how we feel, and shift our perspective so that we can take the right kind of action. Spending time uncovering our true desires, as well as our painful thoughts and emotions, is essential if we want to create healthier ways of relating to ourselves and the world.

If you feel curious and would like to go on an inner journey of growth and self-discovery, get the book or listen to it on audible. It will give you profound insights into your needs, behaviours, thinking patterns, and emotions so that you can reduce stress and infuse more joy and meaning into your life.

| “How to Do the Inner Work is brimming with insight, inspiration and powerful tools that free us from a lifetime of conditioning and trance. When we embrace the life that is here in every moment, we uncover the heartspace that is our true home.” -Tara Brach, author of Radical Acceptance and Trusting the Gold “Madsen writes with a lot of love and practicality, sharing from the perspective of someone who is dedicated to walking their talk.” -Sharon Salzberg, Author of Lovingkindness |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed